The CO2 challenge

With more than 20 million households reliant on gas heating, and current new build properties stubbornly stalled at around 200,000 per year, it would take 100 years to displace the current inefficient housing stock with high energy efficient housing.

So, to make any significant reduction in UK CO2 emissions, the UK must make energy saving in existing buildings and housing a priority.

These savings can be partially achieved via remedial measures such as insulation and double glazing, but the government is also likely to accelerate the decarbonisation of the housing stock by incentivising the take up of heat pumps in preference to gas boilers.

The heat pump conundrum

Older existing properties are less well insulated and less well sealed than new build properties and so consume more energy, and thus produce more CO2. They would benefit the most from energy saving measures.

However, older existing houses present challenges to the introduction of heat pumps as their heat losses are higher,

producing a higher heat demand of the system. Compared to a boiler, heat pumps produce ‘low grade’ heat – typically 40~50°C,

compared to a boiler’s at 70°C – and so are less well suited to heating an older property.

How to square the circle?

Emitters – a matter of degree

With a lower grade of heat available, there are limiting factors in the choice of emitters.

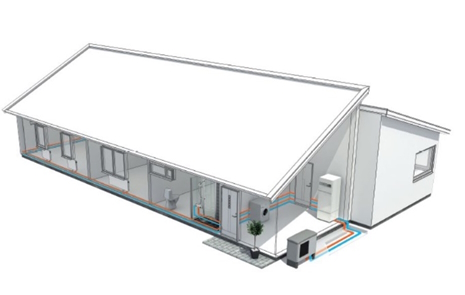

Underfloor heating (UFH) is seen as the natural partner of heat pumps, as it is has to be limited in its operating temperature if it is to avoid damaging the floor structure or surface covering. A UFH system generally operates at between 40°C and 45°C, creating a surface temperature of between 27°C (wooden floor coverings) and 35°C (tiled surfaces). This equates to between 55 watts per square metre and 80 watts per square metre of heated floor (figures of 100 watts per square metre are often quoted, but this is usually before the surface covering is applied).

In older, drafty properties this is often not enough, and, of course, requires considerable work if the floor is already finished and covered.

Whilst UFH is relatively straightforward to install in a new build with concrete screed or a new extension with a tiled floor, it becomes significantly more problematic if it’s a retrofit project, or if wood, laminate or carpet are the preferred final covering.

Oversized radiators

If upheaval is to be avoided, one solution is oversized radiators – basically just a bigger version of the existing radiator to compensate for the reduction in flow temperature. Whilst from a plumbing point of view this is the easiest solution, it is not without its drawbacks.

With space often at a premium, giving over even more wall and useable floor space to a radiator probably wouldn’t win many plaudits from the homeowner; most are trying to either hide the radiator with decorative covers or, preferably, lose it all together. Fitting one which may be up to twice as large, just to accommodate the use of a heat pump, may meet with some resistance.

Secondly, despite being universally know as radiators, most radiators are in fact convectors, in that they rely more on air movement (or convection currents) to distribute the heat around the room than infra-red radiant heat. Radiators rely on a higher differential in surface temperature to the air around them to create the lift or thermal currents that moves the warm air around.

With a surface temperature of 40°~45°C, the difference is not that great (approximately half that of a normal boiler and radiator system) and so the convection currents created are much weaker. This can result in a phenomenon known as micro-climating whereby the warm air mainly circulates in close proximity to the radiator itself due to the lack of lift, resulting in poor distribution of heat.

In some cases, this has led to developers fitting two, and sometimes three, low temperature radiators around the main living spaces to combat the poor heat distribution.

Fan assisted radiators

In order to reduce the installed size of the radiator, some manufacturers have produced smart or fan assisted radiators. They compensate for the lower water temperature produced by the heat pump by using a fan to blow air drawn into the housing across a heating element, and then out through the grilles on the top. This has the advantage of improving the heat distribution by projecting the warm air and reducing the overall size of the unit compared to a conventional oversized radiator.

However, there is the need for an electric supply (to power the controls and the fan), meaning a straight swap from a conventional radiator is not always possible, and the fans may cause disturbance if located in a bedroom.

Aesthetically, fan assisted radiators may not be to everyone’s taste and they will still occupy wall space and limit furniture positions in the same way that the conventional radiator they replaced does.

Skirting heating

After Victorian cast iron radiators and before mass-manufactured pressed steel radiators and central heating became common place, skirting heating was a relatively popular way to heat a home.

However, it fell out of favour in the 60’s and 70’s as the cost of steel pressed radiator fell dramatically as central heating became mainstream.

Skirting heating survived mainly for use in offices and commercial premises, marketed under the names CopperRad or FinRad and usually utilising aluminium fins or wafers on a central copper pipe, in order to maximise the heat output per foot. Aesthetically they were challenging and prone to infiltration from dust and debris as the air was drawn up from the floor and out of the grilles, or articles were dropped inside.

As insulation levels in properties improved, the heat load required decreased accordingly and a new opportunity to provide an alternative solution to convector radiators emerged. Radiant skirting heating is effectively a radiator (in the true sense of the word) that has been squashed and stretched and formed to look like a conventional skirting board profile.

The advanatges of taking up no wall space, having a low water volume, thus being very responsive compared to UFH, and being a simple above ground installation means they are a very practicable emitter to be used with a heat pump.

Which emitter is right for your heat pump project?

ü = very suitable/correct ü = suitable/correct with caveats û = not suitable/correct

|

Feature and benefits |

Underfloor heating |

Oversized radiators |

Fan assisted radiators |

Skirting heating |

|

Suitable for air and ground source heat pumps |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Suitable for new build projects |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Suitable for retrofit and renovation projects |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Simple replacement of existing radiators |

û |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Low cost |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Works as well with any floor covering |

û |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Warms the floor |

ü |

û |

û |

û |

|

Fast response times |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Frees up wall and useable floor space |

ü |

û |

û |

ü |

|

Easy to fix/amend |

û |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Silent operation |

ü |

ü |

û |

ü |

|

Example of providers/ manufacturers |

nu-heat.co.uk |

barlo.co.uk |

discreteheat.co.uk |